Despite the many attempts to codify the creative process, it is as surprisingly individualistic as it is human. John Irving, author of iconic works like The Cider House Rules, describes his creative process as writing the conclusion before the beginning. He spends a year or more developing a story, the plot, and a set of characters in his head, writing nothing down, until he has the whole in mind. Then he writes the final paragraph. Then and only then does he start actually putting words down on paper going from beginning to end. His description of the writing process is a fascinating view into the creative act, most fascinating for me because I do it so differently.

I come up with an idea, often in the quiet mind time of the morning shower or the last thoughts as I slow my mind on the way to sleep. It is usually a blurb of an idea, often captured in a few words or a sentence or two. Never more than that. I repeat it over and over again to myself so that I will remember it, because my memory is notoriously terrible. I sometimes work on that idea for a few days, coming back to it, testing whether I still like it, adding a few connections to it, but rarely carrying it much further. I basically write that sentence of two on my brain and hold it there until I have the inclination or the time to actually develop it, compose it. For I am most fascinated not with the original idea but with what will become of it, where it will go, what it will develop into when I start keying it in for real. To me, the thrill is in discovery. It is in running the experiment and finding the result. It is in seeing the working invention. It is in printing the beautiful picture that I have tweaked and messed with. So I find writing not a painful demanding activity but a creative thrilling one that I take joy in. For I never quite know where it will go or what it will produce. I suppose it is the reason I so love asking “What if…” in our spreadsheets. What does your creative process look like? I just learned more about mine!

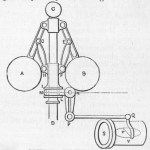

This image of James Watt’s early steam engine shows a variety of inputs, outputs, and connections between them. On the left side, the steam from heating water provides the input to the rule, the big piston outputs the steam into the vertical motion of the piston. That vertical motion, through the rod connecting the piston to the lever, is now a new input. The lever is a rule changing the direction of the motion connecting it to a wheel on the right side. This rule converts vertical motion to circular motion. The lights lines are belts to link the circular motion, yes a link is a rule to drive some other outputs, one of which is the governor. The governor

This image of James Watt’s early steam engine shows a variety of inputs, outputs, and connections between them. On the left side, the steam from heating water provides the input to the rule, the big piston outputs the steam into the vertical motion of the piston. That vertical motion, through the rod connecting the piston to the lever, is now a new input. The lever is a rule changing the direction of the motion connecting it to a wheel on the right side. This rule converts vertical motion to circular motion. The lights lines are belts to link the circular motion, yes a link is a rule to drive some other outputs, one of which is the governor. The governor , that diamond shaped object with two balls attached in the middle of the diagram controls the speed of the engine spreading as it speeds off to reduce the steam output slowing the engine or narrowing to let more steam speed it up. Feedback enables a rule to modify the input based on the output.

, that diamond shaped object with two balls attached in the middle of the diagram controls the speed of the engine spreading as it speeds off to reduce the steam output slowing the engine or narrowing to let more steam speed it up. Feedback enables a rule to modify the input based on the output. Stand and deliver teaching puts the educational burden on the teacher. Students are the recipients of the knowledge in the head of the teacher. I am reminded of this old Egyptian image of Akhenaten’s god. In the paper classroom the teacher’s ability to motivate, to tell a story, to organize, and to simplify the textbook’s knowledge was nearly all of the content available to students. Stand and deliver was a reasonably efficient way to bring the content to the student. Eye contact, proximity, raised hand signals, and easy verbal interaction made this model sufficiently flexible, engaging, and rewarding.

Stand and deliver teaching puts the educational burden on the teacher. Students are the recipients of the knowledge in the head of the teacher. I am reminded of this old Egyptian image of Akhenaten’s god. In the paper classroom the teacher’s ability to motivate, to tell a story, to organize, and to simplify the textbook’s knowledge was nearly all of the content available to students. Stand and deliver was a reasonably efficient way to bring the content to the student. Eye contact, proximity, raised hand signals, and easy verbal interaction made this model sufficiently flexible, engaging, and rewarding.