On this 10th anniversary of the iPhone it is worth remembering that this invention, as world-changing as it was, will not be deemed the most important one of that decade. It will, in the long thrust of history, take second place to an event that truly and profoundly changes the course of human thought. For in this first decade of the second millennium we will be most affected by the democratization* of knowledge. Before this decade, knowledge was rare, a scarce and valuable commodity to be bought, sold, and transferred in schools, workplaces, and books. It was owned by the few and sold to the many. Our schools sold knowledge to students in the form of teacher presentations and textbook descriptions. Our workplaces sold it as apprenticeships, training, and professional development. And our encyclopedias, sold these compilations of all knowledge door-to-door, and libraries were handsomely constructed to give all the opportunity to acquire it in printed form.

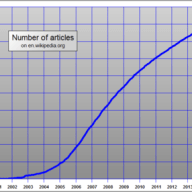

During the first decade of our new century, knowledge ceased to be owned by the elite, ceased to be rare, ceased to be precious. It is now owned by all, ubiquitous, and, for all intents-and-purposes, free. Wikipedia, a tiny but highly significant reflection of this revolution, began in 2001. Its rate of growth, as we can see from this fascinating graph, inflated around mid-decade and is even now slowing down as it has filled up with much of the past knowledge. And Wikipedia is but one of billions of posts and sites that today freely contribute knowledge in every sphere of human endeavor. For knowledge continues to expand at, what to most of us seems like an accelerating pace. Knowledge for the first time in human history, and for as far as we can see in the future, is now democratically produced and distributed.

During the first decade of our new century, knowledge ceased to be owned by the elite, ceased to be rare, ceased to be precious. It is now owned by all, ubiquitous, and, for all intents-and-purposes, free. Wikipedia, a tiny but highly significant reflection of this revolution, began in 2001. Its rate of growth, as we can see from this fascinating graph, inflated around mid-decade and is even now slowing down as it has filled up with much of the past knowledge. And Wikipedia is but one of billions of posts and sites that today freely contribute knowledge in every sphere of human endeavor. For knowledge continues to expand at, what to most of us seems like an accelerating pace. Knowledge for the first time in human history, and for as far as we can see in the future, is now democratically produced and distributed.

From an educator’s perspective, this revolution profoundly changes our job. We can no longer be paid to carefully dole out the precious knowledge, mainly in text form that we acquired from our sweat and treasure, for it is now freely available on the Web. As painful as this may be to those of us who are or have taught, we will no longer be valued for what we know and show, but instead for how we help our students find what they want or need to know.

Applying this to problem solving demands we change our role from telling to asking, from answering to encouraging, from giving to wondering. Our job is now to encourage our students to use the Web to find things out, to learn how to solve a problem, to search for conceptual understanding, to explore possibilities, and perhaps most of important of all, to choose problems of interest to them to practice and build their skills. While students likely know Khan Academy and YouTube videos, most still need to be invited and yes encouraged to use all the tools available on the Internet to solve problems (in our case to learn to use spreadsheets to solve problems). In the digital age, they and their collaborators need to learn to aggressively find and use the digital opportunities to work on and solve problems. They need to learn to separate good from bad, valuable from worthless, helpful from wasteful. They need to be encouraged to find things out for themselves, to try again, to try harder, to keep trying. And they need to be told to get help from their peers and from experts if they need it. They may, of course, at times need some direction, need us to bend their path a bit, but we will have to remember it is their path and not ours!

*I borrow this term, as it applies to education, from my dear friend Jim Kaput.